The view from Barcroft station, at 12,500 feet altitude on White Mountain.

Fresno State physics and astronomy

instructor Brian Bellis explains observing to Fresno State physics professor

Doug Singleton.

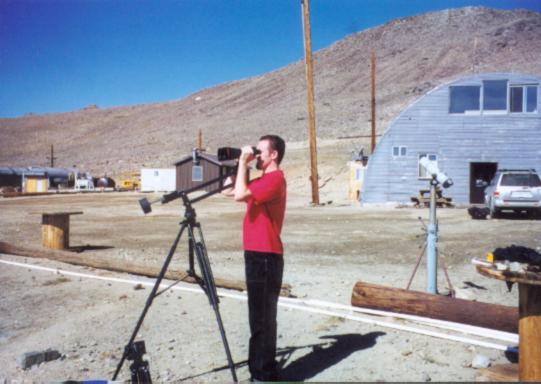

Fresno State student Brian Gleim

tries out the giant binoculars, in front of Barcroft station.

Note the deep blue sky. At night, dark lanes in the Milky Way were full of

detail. Many binocular favorites, such as h and chi Persei, were clearly

visible to the unaided eye. No artificial lights were visible anywhere,

except on the station itself. The only light pollution was a

fifth-magnitude, 5-degree light dome from Las Vegas, some 200 miles away.

Although we all suffered from hypoxia, it didn't seem to affect our

limiting magnitude much.

The expedition gets ready to climb up to

Barcroft Plateau, at 12,750 feet.

The expedition climbs up to Barcroft

Plateau.

A trip to Barcroft station is like

a quick trip to Mars, or to McMurdo Station, near the Dry Valleys of

Antarctica.

The rocks on White Mountain are swept along in

a way reminiscent of a glacial morraine, or on a Martian floodplain.

This shows they have spent much time under snow and ice.

On the way down White

Mountain, the expedition pauses to examine an ancient bristlecone pine.

At up to 4700 years old, these trees are the oldest living things on

Earth.

One reason bristlecone pines can live so

long is their dense wood, seemingly hard as rock. Another is their

networked structure: many have large, dead sections.

Another reason bristlecone pines can live

so long is that they live in rocky soil, full of dolomite limestone.

Fires cannot spread easily here, and there are few competitors at the

treeline at over 10,000 feet. Decay processes are slow, too: logs from

fallen bristlecone pines can be thousands of years old.