The Silk Road and Indian Ocean Trade II

Table of Contents

Text and Images from Slide

- Indian Ocean Trade

- Nature

- Definition

- Partial Shift from

- Silk Road

- Geography

- Geographical extent

- The Ocean

- The Monsoons

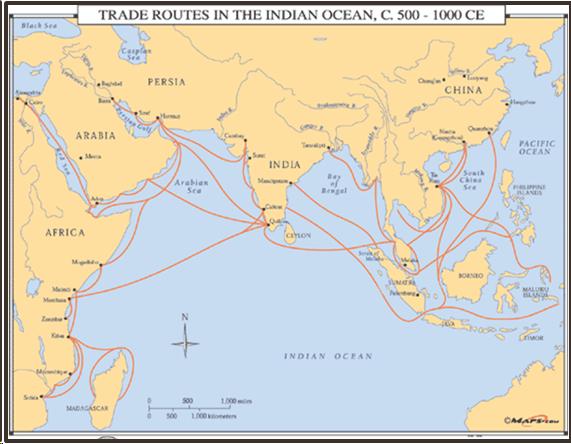

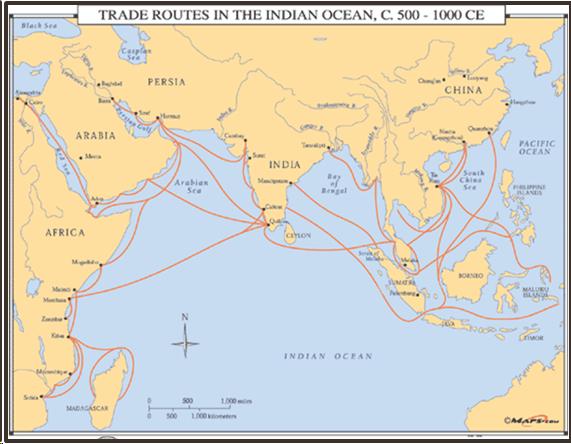

The second major long-distance trade system in the pre-modern world was the network of maritime routes which developed along the basin of the Indian Ocean. Trade had in fact been conducted along the coasts of the Indian Ocean since pre-historical times, and there is evidence to suggest that the Egyptians explored the Indian Ocean as early as about 2300 B.C.E. / Already in full swing by the turn of the first millenium C.E., trade along the basin of the Indian Ocean was boosted by the partial shift south of many trade enterprises from the overland routes of the Silk Road, following the fall of major empires which had previously not only fuel the demand for traded goods, but also offered a degree of ease of travel and security within their territories. The partial commercial shift south was also the result of the increase in the transmission of disease along the overland routes of the Silk Road. / Trade along the Indian Ocean basin then multiplied exponentially roughly around 1000 C.E., both in terms of the amount and variety of goods traded. At the core of this rise in commercial activity seems to have been an explosion in agricultural production around this time, which led to three significant developments in the lands lying on the Indian Ocean. The first was a huge demographic increase in the area, characterized by China's growth by 1200 into the most populous territory in the world, with over 100 million inhabitants, followed in size by another Indian Ocean territory, the Indian sub-continent, which came to have about 80 million inhabitants. The second significant development was increased economic diversification, including particularly the growth of local manufacturing for export, which led naturally to the growth of commerce. Finally, the area experienced as well a significant degree of urbanization and urban growth, as port areas grew into large and sophisticated cities catering to the needs of merchants and investors, both native and foreign. / As was the case with trade along the overland routes of the Silk Road, commerce on the Indian Ocean was shaped to a very great degree by its geography and climate, which presented their own dangers and challenges and therefore dictated trade patterns. The third largest of the world's oceans, the Indian Ocean touches Asia, Africa, Australia and Antarctica. It also connects and links the Continents called the Old World, in contrast to the New World, which is touched by the Atlantic, Pacific and Arctic Seas. The Indian Ocean covers about 26 million square miles, which equals about a 20% of the world's ocean surface. The sheer extent of the ocean presented unique challenges, necessitating not only special ships, but also trade in segments, with ships navigating the ocean in stages, stopping along the route both to trade and to get provisions needed for the next leg of the voyage. / Of course, the Indian Ocean region is larger than the body of water itself, since the region also includes the coastlines where people live to this day, working on and from the sea. It also includes waterways that connect to the Indian Ocean, linking important places where trade originated and distant ports where goods were carried. The larger region important to the story of the Indian Ocean includes three bodies of water in the west which linked Europe, Africa and Asia: the Arabian (Persian) Gulf, the Red Sea, and the Mediterranean. In the east, the region includes thousands of islands east of the Strait of Malacca, the area between Southeast Asia and Australia that leads to the Pacific, as well as the South China Sea, which connects the Indian Ocean with East Asia, the source of many important products, migrating peoples, cultural influences and technologies that affected life along the basin of the Indian Ocean itself. / I would like to conclude this section by discussing the Indian Ocean's defining climate, particularly two important aspects: its tropical temperatures and its characteristic wind patterns. First, the rim of the Indian Ocean which touches the continents of Asia, Africa and Australia lies mostly within the tropics. This means that all of the ports and bays on the ocean are free of ice all year round. There was no Ice Age in the Indian Ocean, so this zone was always habitable - and navigable - by human populations. The Ice Age did affect the ocean in some ways, most significantly changing the shoreline. For example, during the Ice Age, the huge island group in Southeast Asia was connected to mainland Asia, almost all the way to Australia. That was, of course, no longer the case by the period we are investigating here. Still, what is important to remember is that, for the most part, the Indian Ocean has been inhabited and navigated from very early on in the history of human civilization. The Indian Ocean's second defining climatological characteristic is a pattern of seasonal exchange of air masses between land and sea. This pattern is called the monsoon. During summer, when the land masses are warmed by the sun's heat, air masses over the huge continent of Asia rise, pulling in air saturated with moisture from the Indian Ocean south of Asia. The monsoon wind then blows from the southwest. This means that trade during the summer is easiest from west to east, when ships are pushed along by the wind. This pattern is inverted during winter, when the warmer air masses over the ocean pull in dry air from Asia, and the wind blows from the northeast, facilitating trade from east to west. Equally important, the tropical monsoon climate, combined with natural links across land and sea, made the Indian Ocean a place rich in plants and animals unique to this part of the world. Spices, tropical fruits, rare jungle animals, and sea creatures became rare and exotic products and natural resources that became highly sought-after and valued items of trade.