The Silk Road and Indian Ocean Trade II

Table of Contents

Text and Images from Slide

- Beyond Trade Goods

- Religion

- Silk Road

- Buddhism

- Christianity

- Indian Ocean

- Islam,

- Hinduism

- Judaism

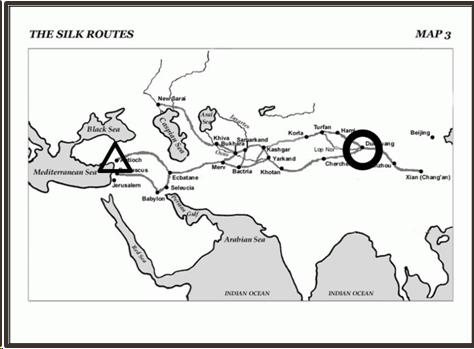

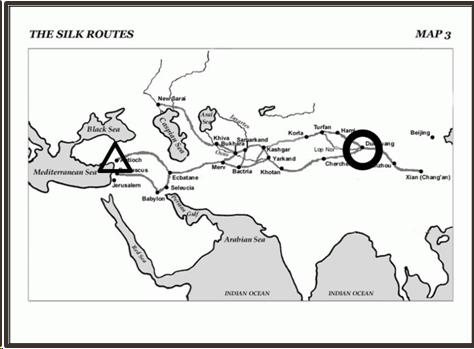

Throughout this lecture, I have mentioned repeatedly that more than just material goods were exchanged along the routes of both the Silk Road and the Indian Ocean basin. While these material goods significantly changed everyday life in the " Old World" - by introducing new flavors, new smells, and new colors to people's experiences, among other things - nevertheless, the influence of tangible commodities pales in comparison to the influence exerted by a series of intangible goods imported by merchants and immigrants to trading posts along the commercial networks. I am referring here to new ideas, including technologies, political approaches, social hierarchies, and cultural traditions. For example, Sub-Saharan kingdoms in Africa embraced Islamic ideas of rulership, while French artisans embraced Chinese techniques for silk production. Likewise, maritime technologies, including the specially designed dhow, a deeper-bottomed ship with a large sail ideal for maximizing use of monsoon winds, were adopted around the whole Indian Ocean. / Among the ideas exchanged along pre-modern trade routes, the most significant was religion. Imported, so to speak, by peoples traveling along both the Silk Road and Indian Ocean basin, many of the major religions about which we have spoken in this class migrated extremely long distances, becoming, in fact, global. Along the Silk Road, Buddhism and Christianity gained new influence, while along the Indian Ocean basin it was Islam, Hinduism, and Judaism which gained new converts. / In this last section of my lecture, I want to concentrate on the spread of Buddhism, which although originally a religion of India became a truly influential religion not there, but in the eastern stretches of the Silk Road, most importantly China and Tibet. The first Buddhist influences came as the passes over the Karakorum were first explored. The Eastern Han emperor Mingdi is thought to have sent a representative to India to discover more about this strange faith, and further missions returned bearing scriptures and bringing with them Indian priests. The greatest flux of Buddhism into China occurred during the Northern Wei dynasty, in the fourth and fifth centuries A.D. This was at a time when China was divided into several different kingdoms. Rulers encouraged the development of Buddhism, and more missions were sent towards India. The new religion spread slowly eastwards, through the oases surrounding the Taklimakan, encouraged by an increasing number of merchants, missionaries and pilgrims. Many of the local peoples adopted Buddhism as their own religion. Faxian, a pilgrim from China, records the religious life in the Kingdoms of Khotan and Kashgar in 399 C.E. in great detail. He describes the large number of monasteries that had been built, and a large Buddhist festival that was held while he was there. Some devotees were sufficiently inspired by the new ideas that they headed off in search of the source, towards Gandhara and India; others started to build monasteries, grottos and stupas. This means that Buddhist influence extended beyond religious faith itself, to art and architecture. For the archaeologist grottos built along the Silk Road are particularly valuable sources of information about the Road and the peoples who traveled along it. Along with the images of Buddhas and Boddhisatvas, there are scenes of the everyday life of the people at the time. Scenes of celebration and dancing give an insight into local customs and costume. These scenes depict both locals and newcomers, the new ethnic diversity of these areas captured in paint. The influences of the Silk Road traffic are therefore quite clear in the mix of cultures that appears on these murals at different dates. / The Buddhist faith gave birth to a number of different sects in Central Asia. Of these, the `Pure Land' and `Chan' (Zen) sects were particularly strong, and were even taken beyond China; they are both still flourishing in Japan. / One last word about the religions of the Silk Road: Christianity also made an early appearance on the Silk scene. The Nestorian sect was outlawed in Europe by the Roman church in 432 C.E., and its followers were driven eastwards. From their foothold in Northern Iran, merchants brought the faith along the Silk Road, and the first Nestorian church was consecrated at Changan in 638 C.E. This sect took root on the Silk Road, and survived many later attempts to wipe them out, lasting into the fourteenth century. Many Nestorian writings have been found with other documents at Dunhuang and Turfan. Manichaeism, a third century Persian religion, also influenced the area, and had become quite well developed by the beginning of the T'ang Dynasty.