Lecture Notes

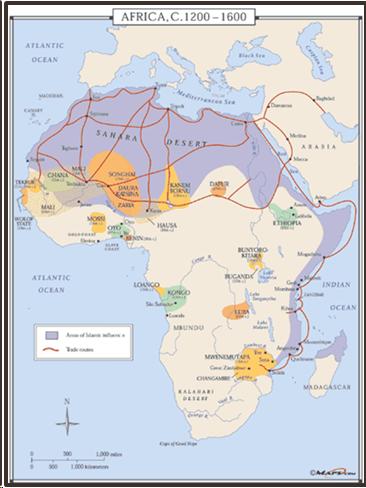

The last major area involved in Indian Ocean trade is made up by the many kingdoms which populated the African continent during this period. Resulting in an incredibly diverse continent, in the pre-modern world Africa was divided into hundreds of small states and a few major empires, including Egypt in its Hellenistic, Roman and, Caliphatic versions. These states collectively played a key role in the global economy of the pre-modern world, up to around 1500 when, as I've mentioned before, the focus shifted to Atlantic trade. Among the African areas most involved in long-distance trade, I would like to introduce three. / The first is perhaps the most obvious, that is, the coastal areas along Africa's eastern shores, which are known as the Swahili Coast. This region was made up of independent city-stated purposely developed and organized around trade. The area's city-states, among which the most significant were Zanzibar and Mogadishu, had three core commonalities which differentiated them from other African states. The first commonality is their language, Swahili. The second commonality is that, although mainly organized by the native inhabitants, all of these city-states evolved into ethnically and culturally diverse areas, populated by peoples from all around the Indian Ocean basin and the African interior who had concentrated in these coastal areas to work in commerce and its related trades. The third commonality is that, unlike other African areas, the city-states on the eastern coast of Africa were religiously diverse and relatively tolerant. In fact, although most of the rulers of these states had converted to Islam by around 1000 B.C.E., they nevertheless welcomed non-Muslims to trade, live, and worship in their cities. / In counter-clock fashion from the eastern coast of Africa to the western, the second major area involved in Indian Ocean trade was Egypt. Throughout its history, Egypt was involved in trade around both the Mediterranean basin and with the Near East, as well as along the eastern coast of Africa. Egyptian commercial involvement in Indian Ocean trade expanded particularly during the period of the Fatimid Caliphate, from the tenth to twelfth centuries C.E., and the subsequent Mamluk Sultanate which lasted into the sixteenth century. Egypt had always played a key role in regional trade networks in the eastern Mediterranean, the Nile Valley, and North Africa. In the early Islamic period, however, only a trickle remained of the important commerce once carried between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean via the Red Sea and Roman Egypt, it being instead shipped through the Persian Gulf and Iraq. Nevertheless, by the tenth century these patterns of trade had begun to shift once again. In the Fatimid period, which is dated from 969 to 1171 C.E. a newly vibrant "international" trade network developed which was shipping goods to and from Egypt, directly reaching lands as far apart as Southern Europe, the Yemen, East Africa, and India, and then by further links Northern Europe, Southeast Asia, and even China. By the later Fatimid period, Egypt had become the crossroads of an extensive long-distance trade system that would endure for centuries. The credit for this remarkable commercial prosperity has sometimes been given to Fatimid economic policies, and these did provide many of the essential ingredients for a flourishing trade. The security of merchants' lives and property was generally guaranteed, and the Fatimids established a gold coinage of such a consistently high degree of fineness that it was widely accepted as currency. The government did reserve the right to purchase certain goods by preemption, and for reasons of both security and revenue it was heavily involved in the trade of particular commodities (especially grain, war materials, flax, and alum). Moreover, government officials were often personally involved in trade. Yet, there was otherwise little state interference in the market, encouraging private investment and direct involvement in trade. While customs dues provided the Fatimids with considerable income, they were not usually excessive, and rates could be surprisingly flexible when the purpose was to encourage trade with particular states or in certain types of merchandise. Egypt's increased involvement in trade was also due to increased demand, particularly from Europe, for goods such as Egyptian flax and alum for use in the textile industry, as well as other Egyptian products like sugar, and also becase of European interest in the luxury merchandise coming through Egypt from the Indian Ocean world. / Moving along to the northeastern territories of the African continent, we encounter what are known as the internal Saharan states, small but powerful and wealthy kingdoms shaped in great part by their involvement in long-distance trade. Although located across the continent from the Indian Ocean, during the first millennium B.C.E. these states profited from trading networks that extended inward from the ocean and across the Sahara Desert. During much of the classical period, links between sub-Saharan Africa and the civilized cores were limited, but between 800 and 1500 C.E. contacts between Africa and other civilizations intensified. As a result, many of the African states converted to Islam, which more closely linked Africa to a Eurasian system of trade, and exposed the emerging states of Africa to new concepts of religion, commerce, and political organization. / As diverse as all these different areas of Africa were, they were connected by the expansive system of trade networks which crisscrossed the southern hemisphere of the "Old World", through which they came to exchange not only material goods, but also ideas.