Control of asynchronous insect flight muscle

The wing strokes of beetles, flies, and wasps and bees are not

individually triggered by nerve impulses; rather, delayed

stretch-activation allows the flight muscles to oscillate spontaneously

when coupled to a resonant load [1]. In this way an agonist-antagonist

muscle pair drive the thorax and wings during both halves of the

wing-stroke. The absence of a separate ‘function generator’ to define

the flapping kinematics is advantageous because simplicity, speed, and

autonomy of the control system are key.

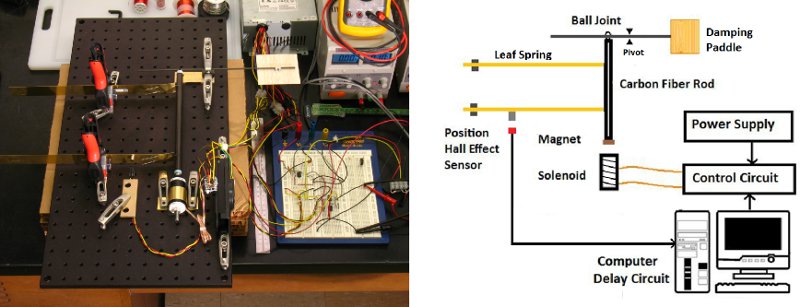

Robot. We have designed

a flapping mechanism by analogy to the asynchronous

flight muscles found in insects of the higher Neoptera.

Our model is driven by a solenoidal linear actuator, which

intrinsically mimics the force vs extension properties of muscle.

Current to the solenoid is controlled by the output of a Hall-effect

position sensor.

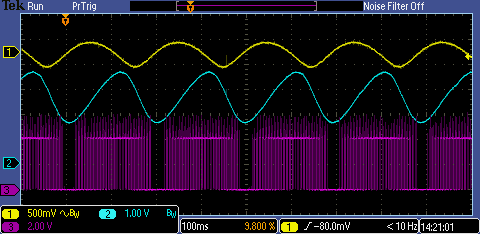

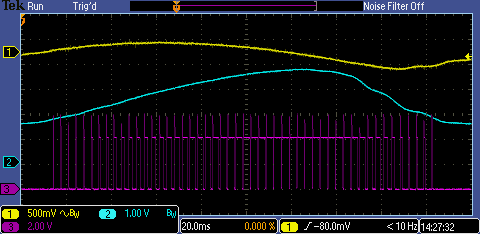

The action of the control circuit can be seen in the oscilloscope traces below, where yellow is the position sensor voltage, blue is the delayed feedback, and purple is the feedback converted to pulse-width-modulation drive signal for the solenoid:

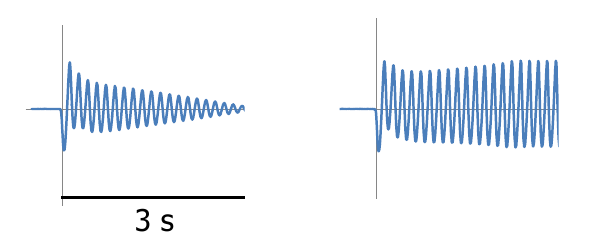

Depending on magnitude of the delay, an initial "kick" of the oscillator is either damped or amplified by the feedback. The traces below show the position of the oscillator (as recorded from the Hall effect sensor) over a 3-second period, for different values of feedback delay:

In the right-hand trace, amplitude grows until limited by contact with the solenoid. It is convenient to characterize such traces with a single parameter, namely the decay constant of an exponential function that best describes the maximum-amplitude envelope:

exp(constant×time)

The break-even point for sustained oscillation occurs when the

constant = 0. Plotting its value as a function of delay (blue

dots below) shows that sharp resonances of effective feedback occur

with a periodicity equal to the natural period of the oscillator, in

this case 1/

(5 Hz) = 200 ms.

Several characteristics of this oscillator are evident in the

functional design of asynchronous insect flight apparatus:

In contrast to synchronous flight muscles, the action of asynchronous ones has a minimal effect on stiffness – a prerequisite for this mode of control, which benefits from a high-quality resonator. The frequency is not affected by damping.[4]

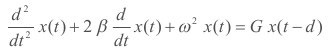

Mathematical Model. Delayed feedback is described by an equation of motion that is non-local in time [2]. The left side of the ollowing equation represents an inertial force, damping force, and harmonic restoring force:

On the right is a force acting against

the displacement, proportional to its value at an earlier time.

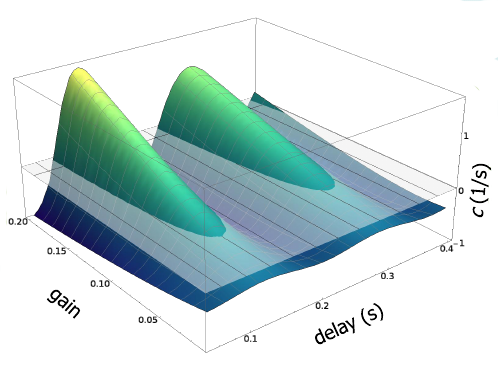

Specific

cases are solved by numerical

integration. The envelope decay constant is plotted below as a

function of delay and gain. The first two regions of

positive feedback are prominent, and they increase in amplitude with

increasing gain (as expected). The solid curve in the plot above

corresponds to a slice in the c-vs-delay

plane below.

We have tested the effects of feedback delay, restoring force, and damping on both the mechanical and mathematical models.

This project considers the phenomenon of delayed-feedback oscillation from three perspectives: robotics, mathematics, and insect flight. Taken together, these systems show promise as a flexible test bed for the investigation of distributed (vs central) control of flapping motion in machines and nature.

References:

[1] R K Josephson, “Asynchronous muscle: a primer” Journal of Experimental Biology 203 (2000) 2713

[2] S A Campbell et al “Complex dynamics and multistability in a damped harmonic oscillator with delayed negative feedback” CHAOS 5 (1995) 640

[3] J E Molloy et al “Kinematics of flight muscles from insects with different wingbeat frequencies” Nature 328 (1987) 449

[4] D L Altschuler et al “Short-amplitude high-frequency wing strokes determine the aerodynamics of honey bee flight” PNAS 102 (2005) 18213